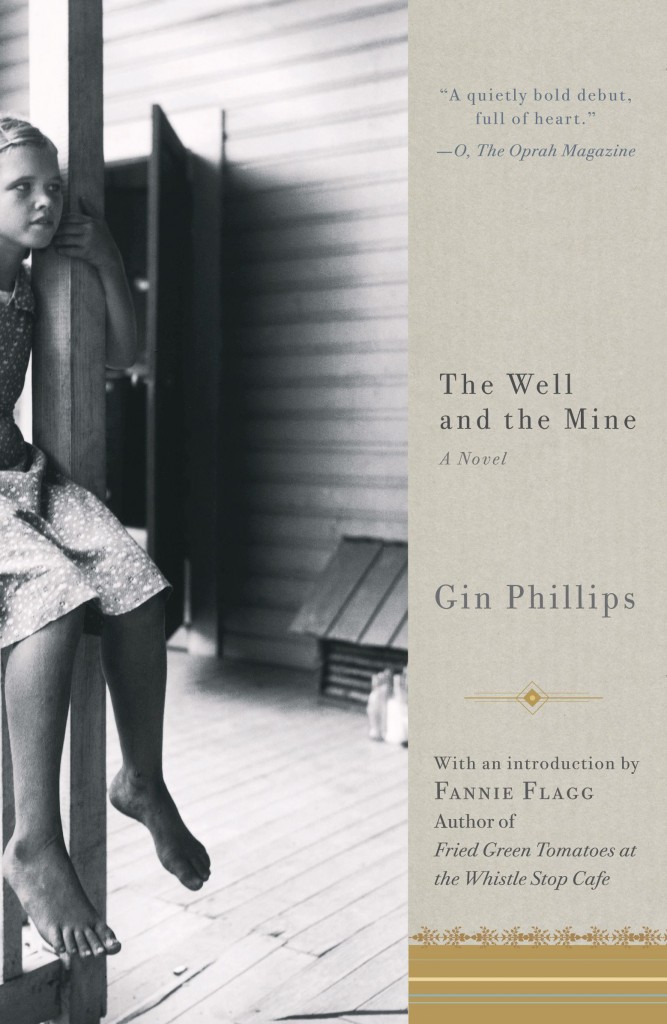

The Well and the Mine

Buy the Book:

Buy the Book:Bookshop.org

Barnes & Noble

Amazon

Books-A-Million

Apple

Published by: Riverhead Trade

Release Date: April 8, 2009

Pages: 304

ISBN13: 978-1594484490

Synopsis

In 1931 Carbon Hill, a small Alabama coal-mining town, nine-year-old Tess Moore watches from the darkness of her back porch as an unknown woman lifts the cover off the family well and tosses a baby in without a word.

It is the height of the Depression, and the Moores are better off than most. Along with most of the men in Carbon Hill, Albert Moore labors in the mines, but he also owns a small patch of farmland which allows him to feed his wife, Leta, and his children during the lean times. The family is also known for being quick to help out with a bit of food or a loan, which makes the choice of their well even more puzzling.

The town is stopped in its tracks by the crime, but it’s Tess who feels the tragedy the most. She becomes plagued by nightmares and feels certain that the dead infant boy is reaching out to her. So her fourteen-year-old sister, Virgie, comes up with a plan to track down the Well Woman. The two make a list of all the women they know who delivered babies in the last six months and begin insinuating themselves into their suspects’ lives. Their investigation doesn’t yield an immediate answer, but it opens the sisters’ eyes to the complications of life beyond their own household.

As Tess tries to unravel the mystery of the woman at the well, a portrait emerges of a family and a community struggling to survive the darkest of times. The Well and the Mine is a stunning novel about love, hope and the importance of doing the right thing.

Why This Book?

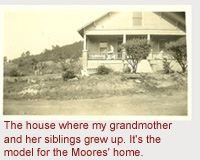

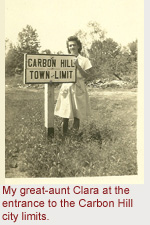

Family is at the core of this book. My grandmother and her three siblings grew up in Carbon Hill, where my great-grandfather was a coal miner. So I grew up hearing anecdotes about life in the coal-mining town. (Let me take this chance to say that I did not hear a single story about a baby down a well—that part of the plot is purely fiction.)

grew up hearing anecdotes about life in the coal-mining town. (Let me take this chance to say that I did not hear a single story about a baby down a well—that part of the plot is purely fiction.)

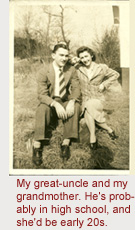

Mostly these stories involved the details of childhood during the Great Depression. I heard the most embellishing from my grandmother and her sister—when they were together, a story became a dialogue. There was the time the two of them made ice cream, and my great-aunt accidentally put cough medicine in it instead of vanilla. (Sugar was precious, so they ate the ice cream anyway.) There was the weekend when my grandmother wore a dress that shrunk in the rain, and the trip to the city when my great-aunt counted trolley cars for an hour before she realized there was only one trolley car going around in a circle.

So I heard all those stories and stored them away. I never intended to use them in a novel. I liked the stories for their own sake. Years later, I started thinking about the possibilities for a story set in an early 1900s mining community. I’d read several nonfiction books that touched on the mining strikes and struggles in the northeastern United States, and I thought of the brutality and danger of everyday life in the mines … and of how the moments of beauty or joy in the midst of all that ugliness would be all the more striking. I thought of how that constant threat of death or disaster—from mining or hunger or poverty or illness—might sharpen your perspective. I thought of how black men and white men worked side by side, and how that companionship inevitably shifted racial attitudes, even in the otherwise-segregated South.

So I heard all those stories and stored them away. I never intended to use them in a novel. I liked the stories for their own sake. Years later, I started thinking about the possibilities for a story set in an early 1900s mining community. I’d read several nonfiction books that touched on the mining strikes and struggles in the northeastern United States, and I thought of the brutality and danger of everyday life in the mines … and of how the moments of beauty or joy in the midst of all that ugliness would be all the more striking. I thought of how that constant threat of death or disaster—from mining or hunger or poverty or illness—might sharpen your perspective. I thought of how black men and white men worked side by side, and how that companionship inevitably shifted racial attitudes, even in the otherwise-segregated South.

Eventually I found myself thinking of a little girl sitting on the back porch of her house, staring out at the night. I knew she would see something come out of the darkness, but I didn’t know what. Or who. As the story of the Well and the Mine began to rise to the surface, I found that even as I tried to see the mysterious Well Woman more clearly and figure out why she would drop a baby down a well, I didn’t have to strain too hard to see the Moore family. Virgie has my grandmother’s sense of propriety. Tess has my great-aunt’s sense of fun. Leta has my great-grandmother’s pragmatism, and Albert has my great-grandfather’s belief in clear-cut right and wrong.

out of the darkness, but I didn’t know what. Or who. As the story of the Well and the Mine began to rise to the surface, I found that even as I tried to see the mysterious Well Woman more clearly and figure out why she would drop a baby down a well, I didn’t have to strain too hard to see the Moore family. Virgie has my grandmother’s sense of propriety. Tess has my great-aunt’s sense of fun. Leta has my great-grandmother’s pragmatism, and Albert has my great-grandfather’s belief in clear-cut right and wrong.

Although the Moores are not my family, they are built with bits and pieces of their real-life counterparts, fleshed out and fictionalized. I know the bonds between Virgie and Tess—I see them even now between my 94-year-old grandmother and her 87-year-old sister. Some of the same family stories I grew up hearing find their way into the Moores’ lives. The sights and smells and sounds of life in Carbon Hill—the red dust in the air, the smell of coffee in the morning, the slick sticky feel of floor cleaner—are details I couldn’t have found in a library. I found them in memories.

Although the Moores are not my family, they are built with bits and pieces of their real-life counterparts, fleshed out and fictionalized. I know the bonds between Virgie and Tess—I see them even now between my 94-year-old grandmother and her 87-year-old sister. Some of the same family stories I grew up hearing find their way into the Moores’ lives. The sights and smells and sounds of life in Carbon Hill—the red dust in the air, the smell of coffee in the morning, the slick sticky feel of floor cleaner—are details I couldn’t have found in a library. I found them in memories.

Reviews

2008 Barnes & Noble Discover Award Winner

2009 Alabama Library Association Fiction Winner

“They are twin black holes of desperation: the family well, down which, one summer night, 9-year-old Tess Moore watches an unknown woman throw her baby, then steal away; and the mine where her father spends his coal-black days. Narrated in turn by Tess, her siblings, and her parents—each haunted by the unfathomable act of that shadow woman—Gin Phillips's novel, The Well and the Mine is part mystery, part meditation on poverty, race, and community in small-town America during the 1930s. A quietly bold debut, full of heart.”

—O, The Oprah Magazine

“‘After she threw the baby in, nobody believed me for the longest time.’ So begins this astonishing debut novel, a story told in the five voices of an Alabama family in the 1930s. Tess, the middle child, is 9 on the night she sees the woman throw a baby into their well. When the baby is found, already dead, Tess and her sister devote their lives to figuring out who the unfortunate woman was. Much like ‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’ ‘The Well and the Mine’ is about the strange contortions forced on humanity by racism and poverty. The family's hometown, Carbon Hill, is a coal-mining town, run largely by a single company. Tess' father works in the mine. During their search for the ‘Well Woman,’ Tess and her sister learn a great deal about desperation and deprivation but also about dignity. Gin Phillips has a remarkable ear for dialogue and a tenderhearted eye for detail; you can hear the pecans and hickory nuts falling from the trees and feel the stillness of a hot summer night. A whisper runs through the novel -- the ghosts of places and people and luscious peach pies, making it a strange combination of dream and nightmare, nightmare and dream.”

—The Los Angeles Times

"Evocative first novel ... moves skillfully between the points of view. With a wisp of suspense, Phillips fully enters the lives of her honorable characters and brings them vibrantly to the page."

—Publishers Weekly

“When you close the book, you'll miss these characters. But The Well and the Mine doesn’t just give you characters who’ll stay with you—it gives you a whole world.”

—Fannie Flagg, author of Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Cafe and Daisy Fay and the Miracle Man

"The Well and the Mine is an enthralling book, enthralling in the best way, without a whiff of showoffy pyrotechnics or earnest sentimentality. Like Willa Cather’s, Phillips’ language is deep, clear, strong, and true; and her characters are at once interestingly familiar, human, refreshingly strange, and complex. The novel’s structure is deceptively sophisticated — the narrative flow is so compelling, it almost obscures the subtle technical skill that went into its making. The Well and the Mine is pure pleasure to read, and achieves the quietest but most rewarding of literary endeavors: a good story, well told. Gin Phillips is truly a great new American writer.”

—Kate Christensen, author of The Great Man

Excerpt

CHAPTER 1

"Water Calling"

TESS After she threw the baby in, nobody believed me for the longest time. But I kept hearing that splash. The back porch comes right off our kitchen, with wide gray brown boards you can lose a penny between if you’re not careful. The boards were warm with heat from the August air, but breathing was less trouble than it was during daytime. Everybody else was on the front porch after supper, so I could sit by myself, nothing but night and trees around me, a thin moon punched out of the sky. The garden smelled stronger than the left- over fried cornbread and field peas with onions. And the breeze tiptoed across the porch, carrying those smells of meals done and still to come, along with a whiff of Papa’s cigarette and snatches of talk from out front. It was the best time of the day to sit with the well, its wooden box taking up one corner of the porch and me taking up another.

I loved the well then.

I leaned against the kitchen door and looked through the wood posts of the railing, even though I couldn’t see anything but black. There weren’t clouds covering that slice of moon or the blinking stars, but they still didn’t throw enough light. The light from the kitchen door let me see to the edge of the porch. But the woman she didn’t see me, I guess. Sometimes the Hudsons down below got their drinking water here—they didn’t have their own well—and I thought it was Mrs. Hudson at first. But she was like a bird, and this was a big, solid woman, with shoulders like a man. She climbed the stairs two at a time. Then she hefted that heavy cover off the well, like a man would, with no trouble. I couldn’t see the baby at first ’cause it was underneath her coat. But she took it out, a still, little, bean-shaped bundle wrapped up like it was January.

I could have reached her in five or six steps. If I’d moved. She held the bundle like a baby for a minute, tucked under her chin like she was patting it to sleep, whispering. The blanket fell back from its head, and I saw a flash of skin. Then she tossed it in. Just like that. Not long after the splash—just a quiet, small sound—she lifted the square cover again and fit it back into its cut-out space, settling it in with careful little touches. Even with all that weight, the porch boards didn’t creak when she left. The splash wasn’t so much the sound of the baby hitting the water as it was the yelp my well made; it sounded shocked and upset knowing something inside it was awful. Wanting my help.

I felt my teeth dig into my bottom lip, maybe drawing blood, but I was quiet as a mouse and stiller than one. Mice scatter like marbles.

After I don’t know how long, Virgie pushed at the door. I knew the sound of her feet on the floorboards. I scooted up, and she poked her head out.

Virgie wore cicada shells, pinned like brooches at her collar. We used to wear them all the time, rows of them like buttons down our shirts during summer, but since she’d be going to the high school next year, she wouldn’t wear them to school no more. She’d gotten too old.

“We’re all out front—why’re you hidin’ back here?” She looked down at me, then up at the well. “I swear, you’d marry that well if it’d give you a ring.”

Beyond it was pitch. The kind of black you think you’d smash into like a wall if you were to run into it. The woman was gone.

“Some lady threw a baby down it,” I said.

Virgie looked at me some more. “Down the well?”

I nodded.

She laughed, and I knew without looking at her she was rolling her eyes. “Hush up and go inside.”

“She did!” My mouth was still the only part of me I could make work—it felt like I’d taken root in the floorboards.

“Nobody’s been near our well. Quit tellin’ stories.”

She knew I didn’t tell stories. I swallowed hard, and it loosened my feet. I pushed myself up and took a step toward the well. “She was, too! A big woman with a baby in her arms. And she threw her baby in without sayin’ a thing.” “Why would she do it with you watchin’ her?” She said it like she was grown-up, not just 14 and only five years older than me.

“She didn’t see me.” My voice was high, and my chest ached with wanting her to believe. At the well, I tried to slide the cover back, but it was too heavy. “Look in here.”

“You don’t have a lick of sense.”

“ Virgie…” I was begging.

She looked a little bit sorry, and came over to stroke my hair like Mama did when I got upset. “Were you daydreamin’? Maybe you saw somebody walk by the porch and you imagined it.”

“No. We have to look in the well.”

“How do you know it was a baby?”

“It was.”

“Was it cryin’?”

“No.”

Finally she looked worried, looking out at the night instead of looking at me. “Somebody mighta thrown some garbage or somethin’ in there outta spite. But who’d do it?”

“It wasn’t garbage. It was a baby. And I’m gone tell Papa.”

I turned and marched off toward the front porch, going back through the house with Virgie right behind me. That last week in August, the nighttime wind was enough to cool your face but not enough to carry off a day’s worth of sunshine. The sun was twice its normal size at the tail end of summer. We’d all stay outside until it was about time to go to bed. Papa and Mama were in their rockers, with Mama shelling peas and Papa smoking a cigarette. They were lit from the lights in the den— Papa was still smudged, even though he’d washed and washed his face and hands. He was bluish instead of black.

Virgie announced it before I could. “Tess says she saw somebody throw somethin’ in the well.”

Papa caught my arm and pulled me over to him. He curled one arm around my waist and set me on his lap. I reached down and felt the leather of his hand, snuggled closer to him.

“What did you see, Tessie?”

“It was a woman, Papa. And she had a baby in her arms, wrapped up, and she threw it in the well.” I spoke slowly and carefully.

Papa used his knuckle to nudge my chin up. “It’s awful dark out back. Maybe you just saw some shadows.”

I shook my head until a curl popped loose from my ribbon.

They were always coming loose. (Virgie had gotten her blond angel hair bobbed to her shoulders and she curled it like in magazines at the newsstand.)

“I saw her. I did. I was sittin’ by the door, and I was gettin’ too chilled so I was gone come in, but then I saw her walkin’ up the back road. I didn’t know her, but she was comin’ right straight here, so I sat and waited and nearly said hello to her when she got to the steps, but then she didn’t walk towards the door at all. She stopped at the well. She looked around, moved the cover, and tossed a baby in. And then she left.”

“I think maybe somebody tossed an old sack of trash or maybe a dead squirrel or somethin’ in there just for meanness,” Virgie said.

I looked straight at Papa. “I swear, it was a baby.”

“Don’t ever swear, Tess,” he said with a little shake of his head, looking back toward the dark. Two lightning bugs went off at the same time.

Mama looked puzzled, the lines in her forehead deeper than usual. “Why would she throw it in our well?” Virgie looked mad at me. “Now you’ve upset Mama.”